The Maestro’s Corner: The Flying Dutchman

Wagner’s Style Emergence

October 8, 2015

Maestro’s Corner

The Flying Dutchman: Wagner’s Style Emergence

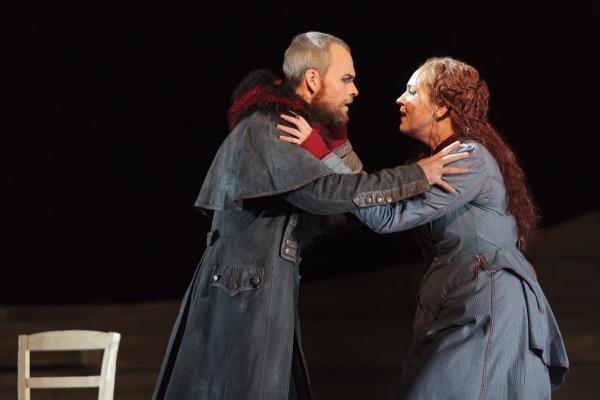

Dresden, January 2, 1843: A brand-new opera premiers. Named Der Fliegende Höllander, or The Flying Dutchman, it takes the operatic world by storm, and its composer, Richard Wagner, has soon risen to modest fame. He had written the score in fewer than two months, and conducted the orchestra himself at this debut of his latest opera. However, The Flying Dutchman differed drastically from the three earlier operas he had composed (Die Feen, Das Liebesverbot, and Rienzi). These first three operas had been penned in the popular Italian style, complete with rapid strings of staccato notes and fluttery coloratura. However, from the moment the curtain rose on The Flying Dutchman, it became obvious that Wagner’s paradigm for composing had changed radically.

Wagner would go on to become the most famous—and controversial—composer of the century. His operas departed completely from the light, superficial tone of the Italian and French operas that had dominated the stage until then. His plots had many psychological layers, and displayed some of humankind’s darkest and most feared emotions. Are his pre-Dutchman operas, so unlike the musical and intellectual masterpieces that he would create later, not classifiable as Wagnerian (that is, not in his special style)? Could it be speculated that The Flying Dutchman is the first real Wagnerian opera? An appraisal of the facts surrounding this extraordinary work will offer an answer.

The Flying Dutchman is the first opera Wagner wrote that showed hints of a talent he would later become famous for: the ability to interpose psychological meaning in an orchestral passage through the reshaping and reiteration of his themes. He had written three earlier works, the two little-known operas Das Leibesverbot and Die Feen, and his first true success, Rienzi. In these operas, however, Wagner did not handle his themes as nimbly as he would later. Other composers used themes, of course; that has always been a part of opera. Nevertheless, in the traditional operas, as well as in Wagner’s first three, these themes simply occurred with predictable regularity whenever their subjects appeared on stage. In his early works, Wagner did not, as he would later, use the themes to make subtle narrative points. The Flying Dutchman is much more delicately crafted. For instance, the themes of The Dutchman (No. 1) and Eternal Wandering (No. 4) not only appear where they would be expected (namely, in the overture and during the Dutchman’s solo aria in the first act) but also in other places where a different theme would have been used by a typical composer: just before Senta’s ballad, for example, and before and during the love duet in Act II. This creates new meanings for both the themes and the context they are used in. In this example, the Dutchman was not onstage during Senta’s ballad, but playing his theme just before the ballad signified that his story was about to be told.

The style of the music in The Flying Dutchman also differed drastically from the customs of the age. Although Rienzi contains a little too much brass to make it sound really Rossinian, it was in The Flying Dutchman that Wagner established the compelling, profound style he would use in his subsequent operas. It shocked old-fashioned operagoers. Instead of beginning with a susurration in the woodwind and violins, or with a major-key chord in the strings swinging into an allegro vivace rhythm, the overture kicks off with a deafening fortissimo octave in D minor, punctuated with sharp fifths. Then, the orchestra, using the Dutchman’s theme as its melodic base, proceeds to emulate a violent but methodical sea storm, with crashing waves in the cymbals, rumbling sails in the drums, and woodwinds screaming angrily through masts and rigging. Having spent itself into a brief moment of tense calm, the storm finally gives way to the other themes. Instead of using light, romantic rhythms and melodies, Wagner proceeds to begin the first act with the hearty Sailor’s Chorus. Unseating tradition again a bit later, the Dutchman’s magnificently tempestuous aria “Wie oft in Meeres tiefsten sclund” could not in any way be conjectured as even remotely Italian. In the second act as well, the a capella lines of Senta’s ballad lend an unorthodox but stunning resonance to the song. At the time, operatic ballads were expected to be accompanied by a rhythmic dance. In another shocking departure from tradition, Wagner assigned the lead role to a dramatic baritone, not the usual melodious tenor! Performed properly, The Flying Dutchman sounds neither clumsy nor overdone, even when compared to the popular, bouncy, Italian operas. Although it does contain a few trite cadenzas, it resembles in no way his three earlier works, but foreshadows the groundbreaking operas that Wagner would compose later.

The demands that Wagner made on the singers of The Flying Dutchman had been unheard-of until that time. Instead of giving the role of Erik the Huntsman to a saccharine lyric tenor, in his Remarks on Performing The Flying Dutchman, he required that the tenor sing the role with not so much sentimentality as with fierce energy and frustrated sorrow. And Senta, he ordered, would have to be performed with a strong-willed simplicity, a stubborn innocence extremely difficult to achieve in music. Wagner also bucked tradition in another way; the vocal passages themselves, instead of containing conventional coloratura flourishes and hummable tunes, have a distinctly non-melodic style. Strings of repeated notes, jumps between staffs, tightly woven themes, and understated tonal contrast made the parts almost impossible for singers used to Italian opera to memorize. Even so, the music was no easier to actually sing: long passages of unaccompanied score, mid-measure crescendos, and notes held for much longer than normal (thanks to plentiful fermatas) demanded both singers and orchestra to possess both unwavering focus and tremendous endurance. Furthermore, absolutely none of the conventional harpsichord-accompanied recitatives made their way into the opera. As Wagner himself affirmed, “It’s all arias!” This approach made it challenging for Wagner to find singers capable of performing his roles. He would struggle with this problem for the rest of his career. He never encountered this issue with his earlier operas, for they were nowhere near as musically ambitious as The Flying Dutchman.

The Flying Dutchman, an operatic milestone, marks a definite change in Wagner’s mode of composing. This work contains the initial occurrences of the psychological leitmotif variations; they have since become his hallmark. It also marks the beginnings of Wagner’s unique musical style, and the birth of the heavy demands on the singers that are now seen as characteristic of his operas. The difference from tradition in musical form has made the most obvious contribution to the concept that The Flying Dutchman marked the genuine start of the Wagnerian style. But why did he make such a drastic change in his style? Rienzi embodies Wagner’s desperate, and ultimately failing, attempt to sound Italian. It has the usual rapid trills in the strings, the florid cadenzas, and many other elements which show that he was keenly attuned to the style of the times and had tried to copy it. However, even before he began composing, a young Wagner had dreamed of creating the perfect connexion between music and stage. The Flying Dutchman was the start of his quest for that dream. Once he had attained fame through Rienzi, he knew that he could risk the departure from style without damaging his career too badly if it ran amok. So, the creation of The Flying Dutchman was not so much a change in style as an unveiling of his ambition. Therefore, the first true Wagnerian opera, and the one Wagner himself regarded as such, is The Flying Dutchman.